Ballet and opera fans, be forewarned. You may never be able to look at such classics as The Nutcracker, Swan Lake, Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades quite the same way after witnessing celebrated Boris Eifman’s searing dance psychodrama, Tchaikovsky. PRO et CONTRA.

But that’s no reason to deny yourselves the thrill of experiencing the celebrated Russian choreographer’s unique blend of contemporary ballet, over-the-top emotional intensity and rampant spectacle. In fact, it might even deepen your understanding of the great composer’s work.

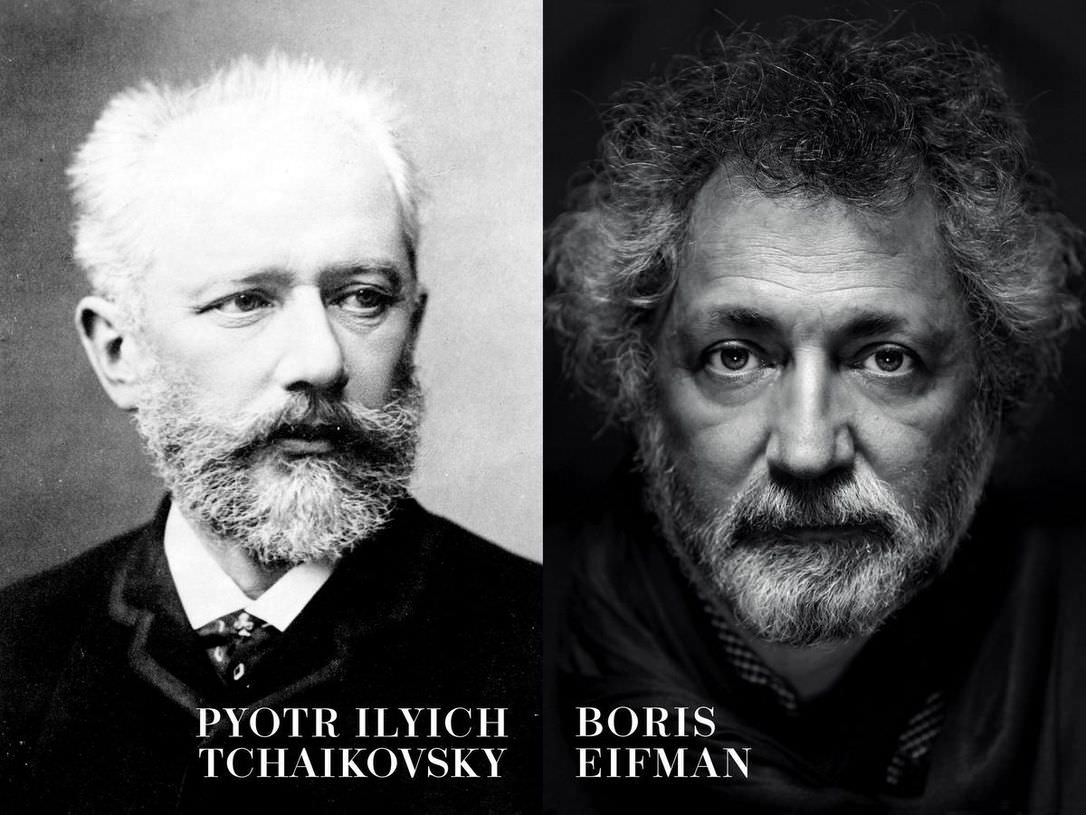

Russian choreographer Boris Eifman, head of Eifman Ballet St. Petersburg, has written a ballet about Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

Eifman, 72, often described as ballet’s most determined psychoanalyst, has always been drawn to tortured souls. Some he exhumes from the pages of literature: Anna Karenina, the Karamazov brothers. Others, such as the sculptor Auguste Rodin and ill-fated ballerina Olga Spessivtseva are drawn from real life. Occasionally Eifman intertwines the two, as in his Shakespeare-inflected interpretation of Czar Paul I’s psychological torment in Russian Hamlet.

An analogous merger of fact and fiction occurs in Tchaikovsky. PRO et CONTRA, which Eifman Ballet St. Petersburg is presenting during the company’s fourth Toronto visit. Real-life characters such as the composer, his wife and his patroness are all portrayed onstage but in Tchaikovsky’s fevered imagination as the ballet unfolds in deathbed flashbacks. They weave their way through his ballets and operas.

Tchaikovsky’s abhorrence for Antonina Milyukova, the woman he unwisely married in 1877 and abandoned only six weeks later, fuels the tragic yearnings of his Swan Lake. Nadezhda von Meck, the wealthy widow who bankrolled and corresponded with the composer for more than a decade, becomes The Sleeping Beauty’s evil fairy Carabosse and the Countess in The Queen of Spades, dealing the cards that spell Tchaikovsky’s fate.

Eifman also invents a double/alter ego for Tchaikovsky. Throughout the ballet this imagined character, whether appearing as Swan Lake’s Von Rothbart, Nutcracker’s Drosselmeyer or as Onegin, serves as a visual manifestation of the choreographer’s basic contention that the composer’s psyche was torn apart. And not just by the inner torments Eifman routinely ascribes to creative artists but by Tchaikovsky’s particular need to hide and repress his homosexuality.

While there is general agreement that Tchaikovsky loved men, an admittedly problematic leaning in 19th-century Russia, the evidence is inconclusive about just how much this troubled him. For Eifman, however, academic history should never be allowed to encumber his more poetic and psychoanalytic insights, or stand in the way of an emotionally riveting story. And, to be fair, something very deep must surely account for the bittersweet, yearning character of so much of Tchaikovsky’s music.

Although Eifman has turned to a broad range of composers since he began to choreograph almost 50 years ago, he has always felt a strong connection to Tchaikovsky.

“I was 6, perhaps 7, when I was taken to see Swan Lake,” recalls Eifman. “It had such a powerful impact, I remember bawling my eyes out. I felt an immediate emotional connection. Now, after many years, I can feel his soul.”

As he expanded his knowledge of Tchaikovsky’s music and learned more about the composer’s life Eifman, by then well established at the head of his own company, decided in 1993 to make him the subject of a new ballet: Tchaikovsky: The Mystery of Life and Death.

At the time, the fact of Tchaikovsky’s homosexuality did not sit comfortably with many Russian admirers of his music.

“People protested the premiere; ‘Hands off our Tchaikovsky.’ I even received death threats,” says Eifman.

Regardless, the ballet went on to become one of Eifman’s greatest international successes but eventually was dropped from his company’s touring repertoire because impresarios, not unreasonably, wanted to offer audiences something different.

Fortunately, Eifman has a habit of revisiting and revising his ballets and, in 2016, returned his attention to Tchaikovsky.

“It was always one of my personal favourites,” he explains, “and I really wanted it back in the repertoire but, when I looked at it, it was very much a 20th-century production. My theatrical approach has advanced in the intervening years. I myself have changed. My choreography has changed. My attitude to Tchaikovsky has changed. So I knew I needed to put on a whole new ballet, which is what I have done.

“I wanted to create a work in which I could delve deeper into the environment of Tchaikovsky’s creative torment.”

Interestingly, although Eifman evokes several Tchaikovsky ballets and operas, he does not attempt to reproduce them. Most of the music he has chosen comes from the symphonies and the Opus 48 Serenade for Strings.

While Eifman’s ballet depicts Tchaikovsky’s 1893 death at age 53 it does not attempt to unravel what remains its mysterious cause. The idea that the composer intentionally drank water contaminated by cholera is unproven. Yet, as he listens to the Sixth Symphony, the Pathétique, whose premiere the composer conducted only nine days before his death, Eifman believes thoughts of suicide had been much in Tchaikovsky’s mind.

“Just listen. That symphony is surely a requiem for himself. I do not believe his death was accidental.”

Despite the popular international following Eifman has acquired, not least here in Toronto, there has always been a strain of resistance to his choreography among critics, even while they praise the athletic power of his dancers. His popularity is almost held up as evidence of a lack of seriousness. Yet nothing could be farther from the truth. For all Eifman’s canny theatricality and heart-on-sleeve emotionalism he is deadly earnest in his intentions. He means every step he makes.

Says Eifman: “I follow my deepest intuitions.”

Eifman Ballet’s Tchaikovsky. PRO et CONTRA is at the Sony Centre for the Performing Arts, 1 Front St. E. May 9 to 11 May. Visit sonycentre.ca or call 1-855-872-7669.

Source: The Star